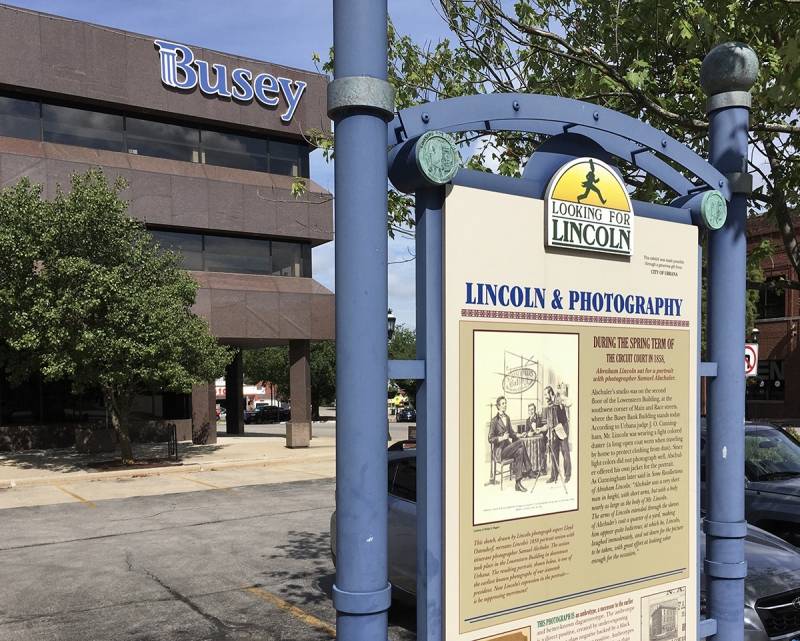

What is the oldest church in Champaign?

The answer to that question depends on what you are looking for. The earliest to organize? The first building to be constructed? The oldest building still standing?

In an earlier post, “Six Historic Churches in C-U,” (part five of the “Historic Sites Re-visited” series), we covered the history of the two oldest congregations in C-U – First Presbyterian and First Congregational churches. Both were originally organized in Urbana (1850 and 1853, respectively); both moved to “West Urbana” (later Champaign) in 1854 and erected their first buildings the following year.

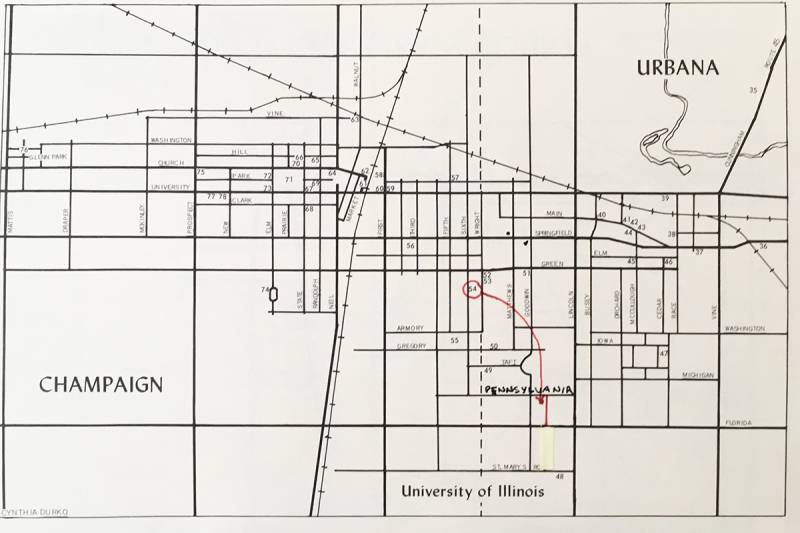

Credit for “first building” in Champaign has generally to the Congregationalist’s so-called “Goose Pond Church” at First and “Main” (now University). First Presbyterian’s fine brick gothic church at the corner of State and Hill streets is the oldest church still in use. Also designated as official Historic Sites in 1976 were Champaign’s Emmanuel Memorial Episcopal, and Salem Baptist churches (the others were St. Patrick and the Wesley Foundation churches in Urbana). The histories of all these congregations are covered in the earlier article. In this piece, we’ll take a look at some other early churches in Champaign.

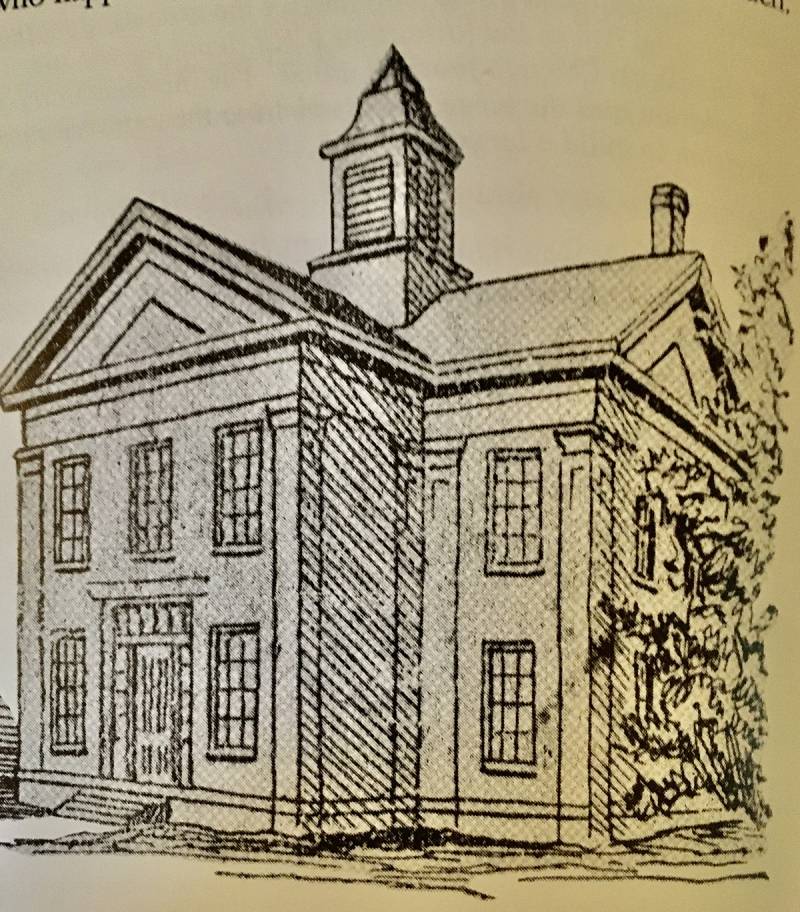

In her 1937 study of early Champaign (portions published as The Beginnings in 1960), University of Illinois grad student and later historian Natalia Belting writes, “Another church built in 1855, on Columbia street, and claimed by some to antedate the Congregational Church, was the German Lutheran . . . .” St. John German Lutheran Church was indeed organized in 1855, but a congregational history places the building construction in 1858.

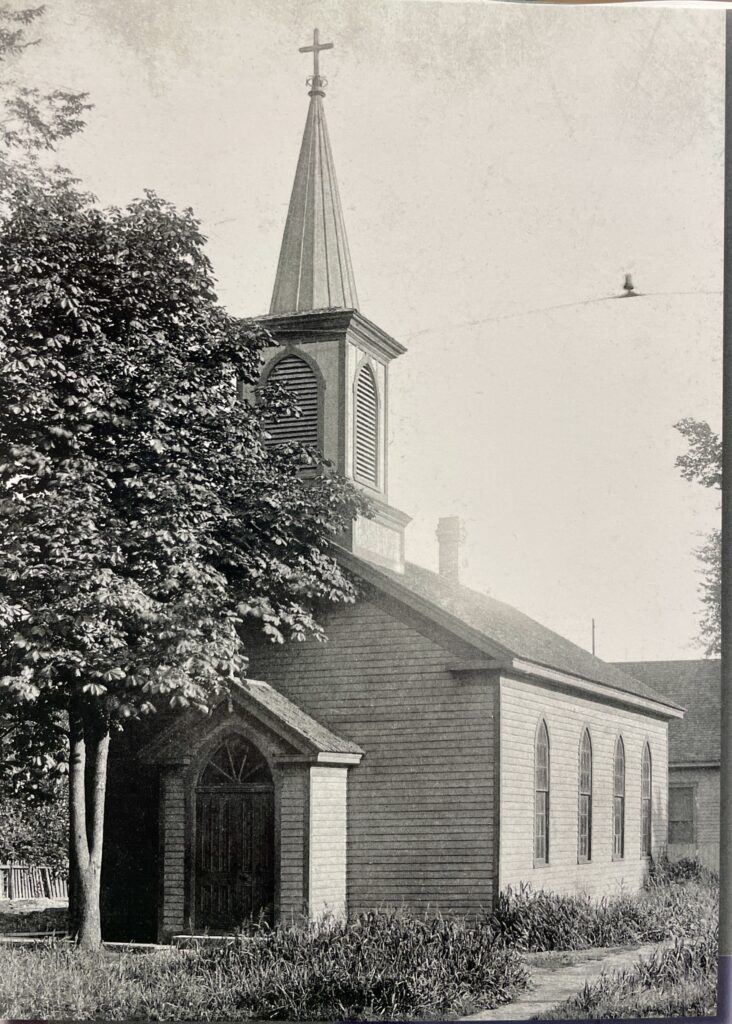

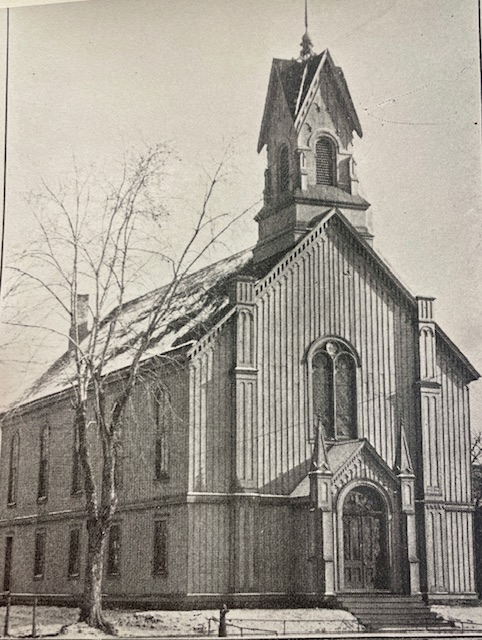

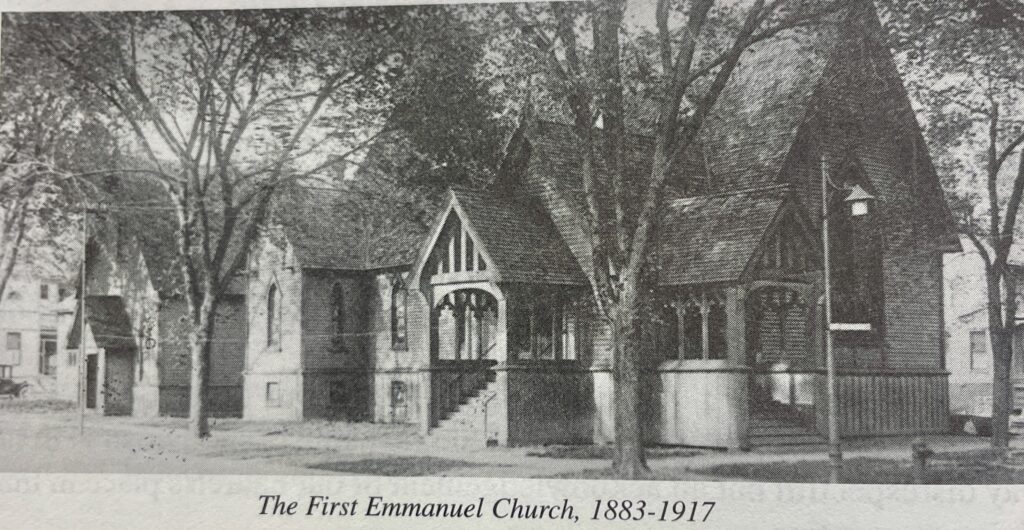

St. John’s small frame church (right) was slightly east of Randolph street on the north side of Columbia. In 1875 the church received a gift of property at the northwest corner of Fourth and University and began using the residence there as a parsonage.

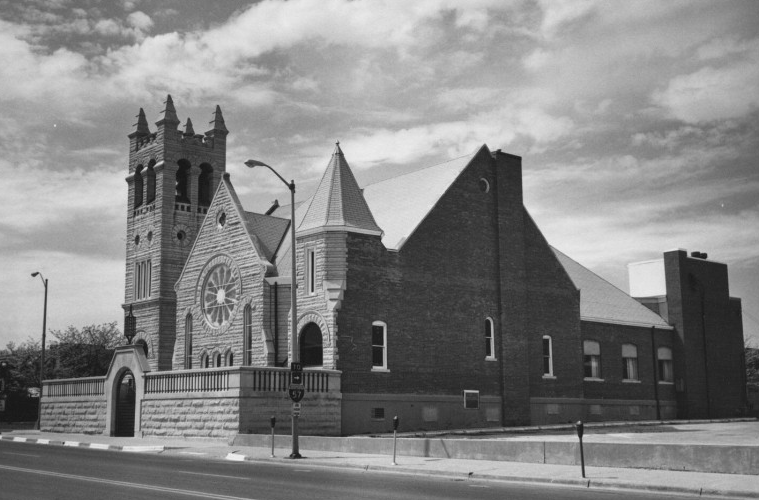

In the early 1880s, the parsonage was razed and construction began on a new church on the site. The church is first shown at that location in a 1883-84 city directory, but the building was not dedicated until February of 1900 (below left). Extensive renovations in 1916 included removing the steeple and adding a brick exterior veneer (below right).

First United Methodist Church in Champaign was surprisingly absent from the 1976 project designating official historic sites in Champaign County. The congregation traces its beginnings to the efforts of pioneer circuit riders who established the “Urbana Station” in 1854. A Methodist “class” began in a home “at the Depot” in the fall of 1855. The first pastor was appointed in 1856 and the “Methodist Episcopal Church” was officially organized (“First” and “Champaign” later).

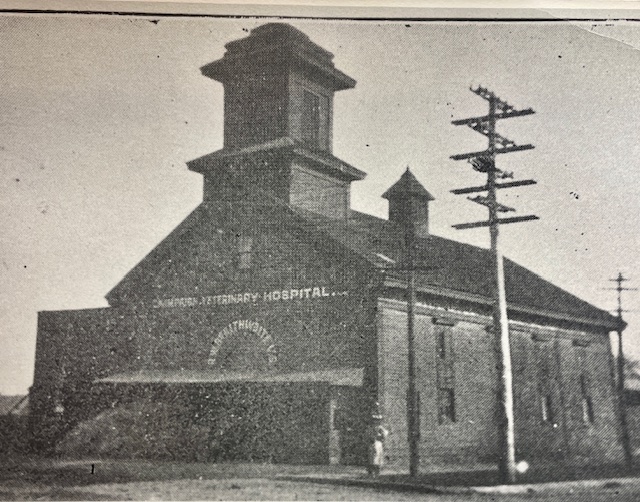

Services were in the Doane House, the Brick School,” and First Presbyterian Church until 1860, when several lots were purchased at the northeast corner of Church and State. Construction began on a wood frame chapel with a cupola bell (below left), completed in 1862. In 1888 the building was moved to the northeast corner of Hickory and Washington, where it housed the Champaign Veterinary Hospital (below right) for several years.

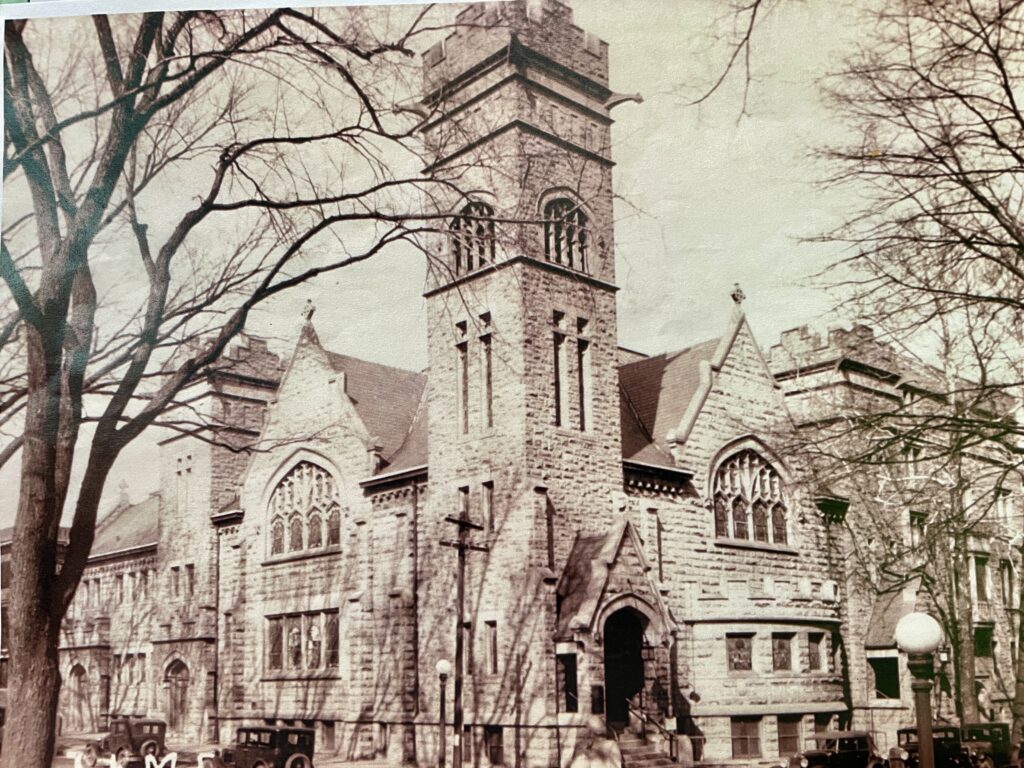

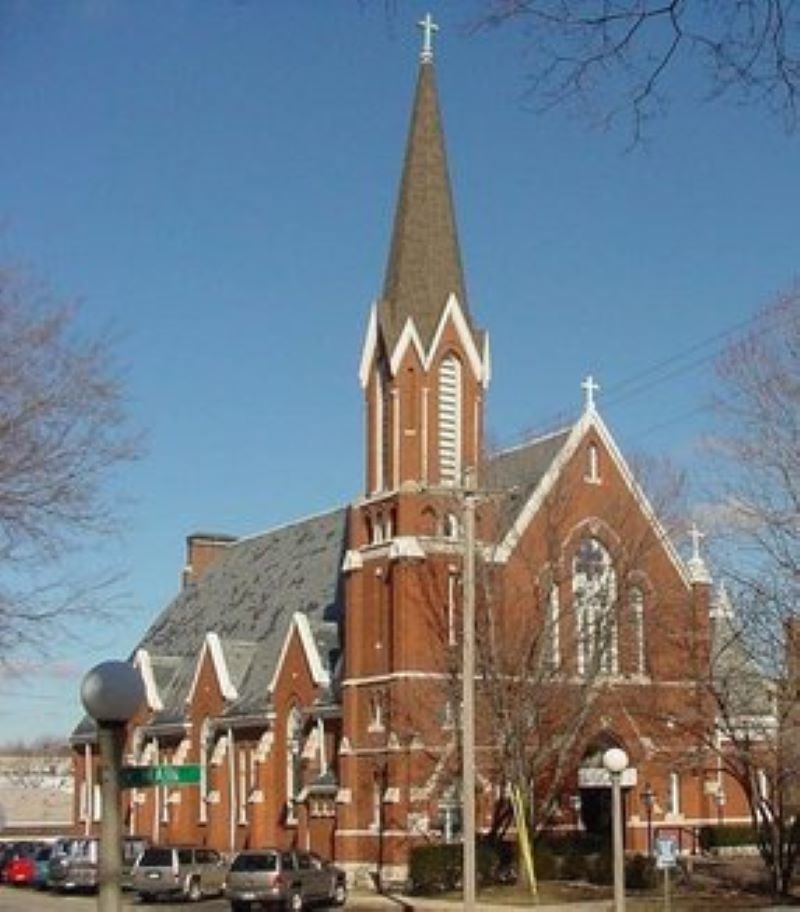

The old frame church was replaced by one “built in brick with Queen Anne Style stone trimmings” and featured a “large tower 85’ high at the corner” (below left). The “Old Brick Church” served the congregation until 1906, when it was demolished to make way for the present “Stone Church” (below right). The new English Gothic style church was dedicated in September 1907. The adjacent multi-story “Parish House” in the same style was added in 1923.

In 1963 the Education Wing was added to the east, and the sanctuary was substantially remodeled. The original fan-style seating, with the pulpit in the northwest was changed to a north-south orientation. The original wrap-around balcony was replaced by a single balcony at the south end.

Another “pioneer congregation” in Champaign still exists, but it is no longer in Champaign. Baptists began holding services as early as 1858 in Bailey’s Hall. First Baptist Church was officially organized on September 11, 1864. The following year, their Park Street Chapel was built at the corner of Park and State, where the parking lot of the Episcopal Church is now.

In 1869 the Baptists moved to a larger frame church (pictured right), located at the northeast corner of Randolph and University (where Busey Bank is now). It served them until the end of the century.

In 1900 the landmark stone Gothic-style church was built on the same site (pictured below). After 80 years at this corner, the congregation moved to Savoy. Downtown property sold; building demolished. One of the beautiful circular stained-glass windows was preserved and still hangs in the church’s present sanctuary.

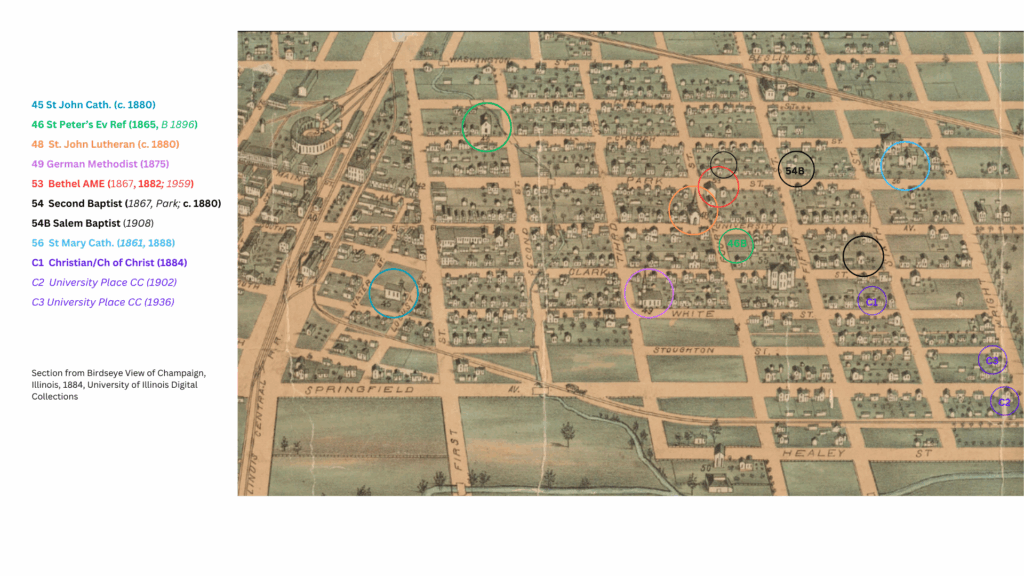

By the end of the 19th century, there were over a dozen churches in town, and more of them were now located on the east side of the Illinois Central tracks than on the west side. The area “across the tracks” from First to Wright, roughly between White and Washington, was home to Champaign’s Irish, German, and African American population. St. Mary Catholic Church was established in 1854 as the “Urbana Mission” to serve Irish and German laborers who were working on the railroad construction project.

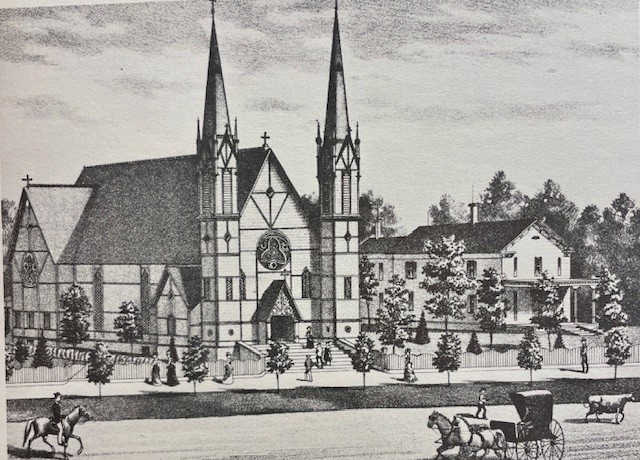

The first St. Mary Church was “a small brick building” erected “in 1856 or 57” on the north side of Park between Sixth and Wright. After it was damaged by a windstorm, construction on a larger “white frame building in the shape of a cross” (pictured at right) began in 1858. This church was dedicated in 1861.

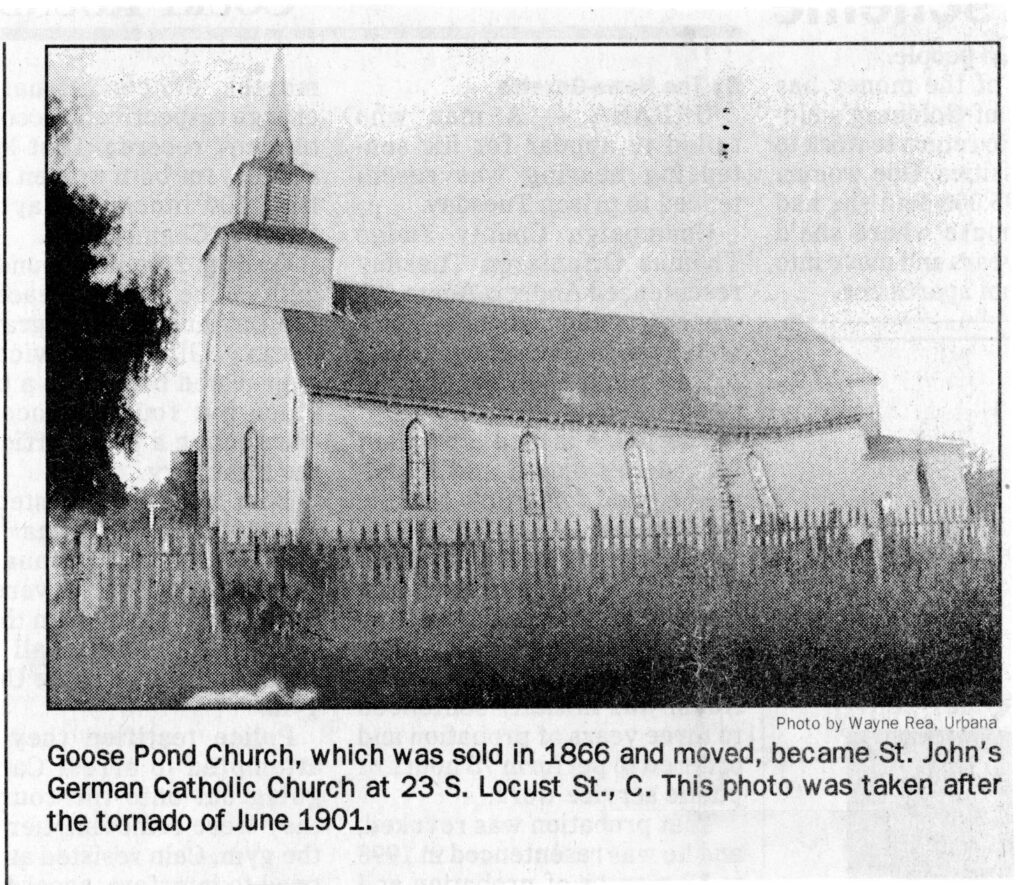

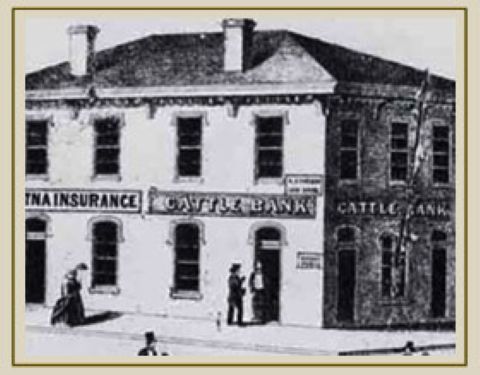

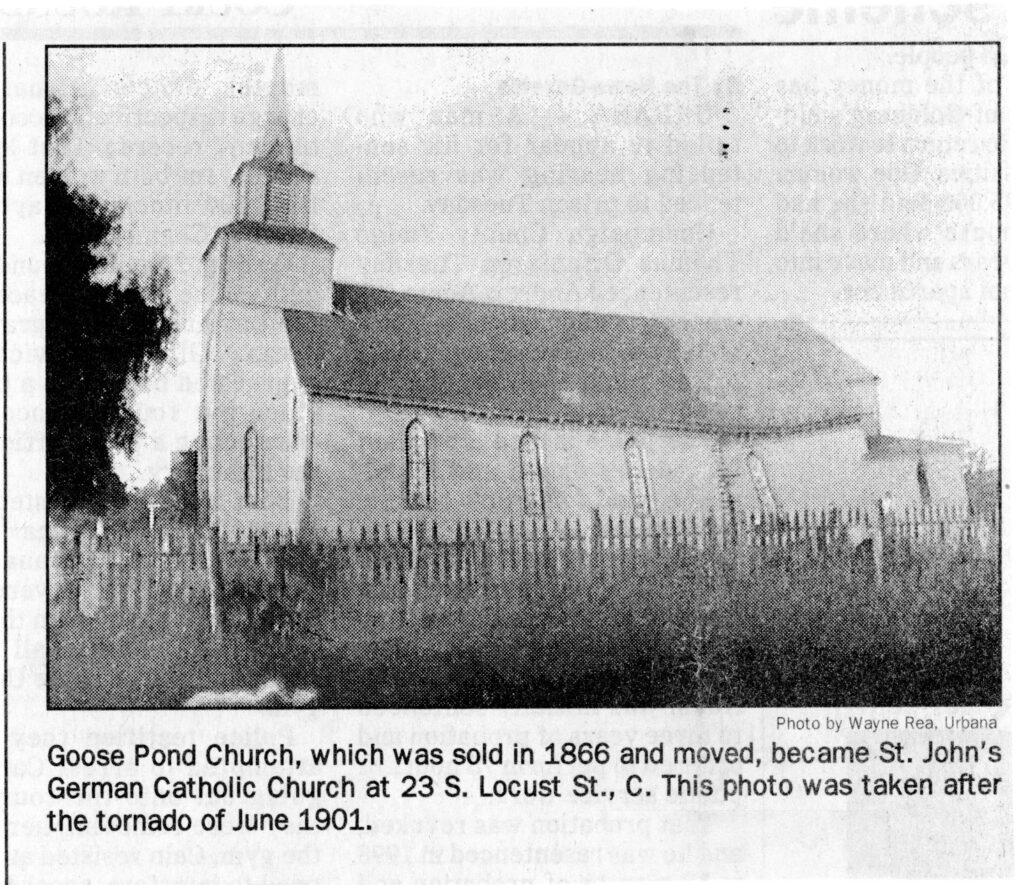

In the 1870s there was a split between the Irish and German parishioners at St. Mary. While mass was in Latin, homilies were in English, and the Germans wanted their own parish which could be served by German-speaking priests. They first moved into the old Congregational (“Goose Pond”) building (pictured right) and organized as the German Catholic St. John Church. In the mid-1880s the church building itself was moved a few blocks south to the west side of Locust Street.

When the present brick St. Mary Church was constructed in 1888, part of the old frame building was moved and added to the rear of the St. John Church, now on Locust Street. The church was severely damaged by a tornado in the summer of 1902, leading to the demolition of the old “Goose Pond” building and construction of a new brick veneer church, dedicated May 25, 1903.

In 1912 St. John became a student chapel for the University of Illinois and eventually relocated to the present building at 6th and Armory on campus in 1926.

In 1875, the German Methodists moved from the original Presbyterian building on Hill St. to a new building at the northeast corner of Third & White (pictured right). Over time, membership gradually shifted to First Methodist. The “Mother Church” bought the Third St. building in 1910 and moved it to the northwest corner of Fifth and Church. For few years, it housed a mission called Fifth Street Methodist.

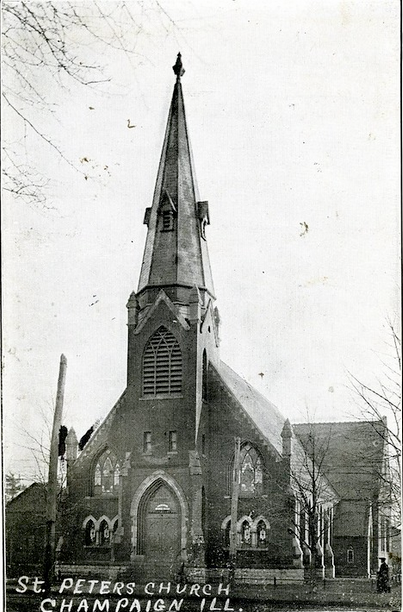

Another German congregation on the “east side,” St. Peter’s German United Evangelical Church, was organized in 1865 “in the heart of what was then the German neighborhood.” A 28 x 40 frame 2-story building erected at the northwest corner of Second and Church was dedicated December 31, 1865.

St. Peter’s was German-speaking church of the Reformed Tradition. It was identified as the “United Reformed Church” in the 1878-79 City Directory. The 1884 Birds Eye map and 1887, 1892 Sanborn maps identify it as the “German Presbyterian Church.”

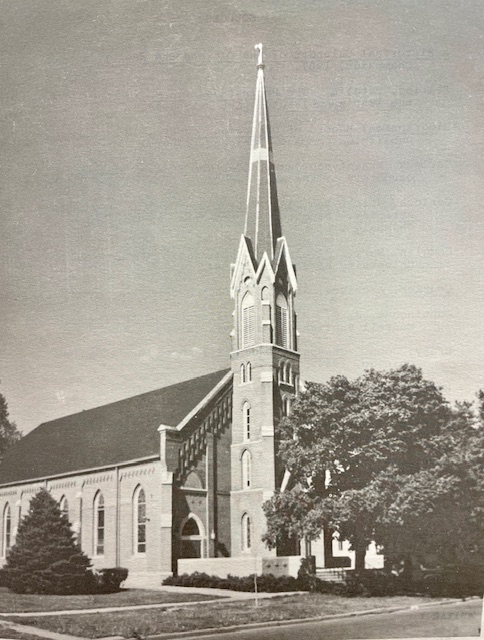

In 1896, St. Peter’s moved to a grand new church constructed on the southeast corner of Fourth and University (pictured left), diagonally across from St. John Lutheran. The two venerable German-heritage congregations anchored this intersection for over 50 years until each moved to their present locations on the west side of town (St. Peter’s in 1957, St. John in 1960).

Both old buildings were torn down. A series of denominational mergers brought St. Peter’s into the United Church of Christ. St. John is affiliated with the Lutheran Church, Missouri Synod.

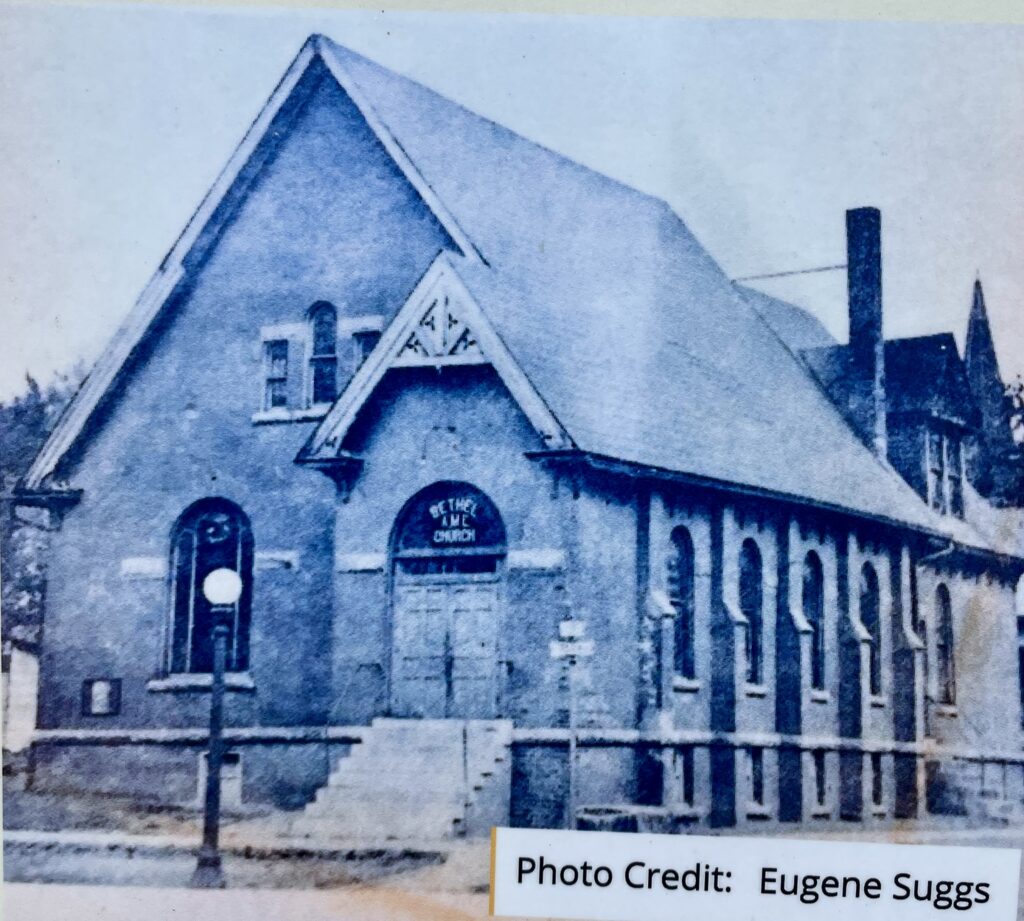

Bethel African Methodist Episcopal (AME) Church, the oldest Black congregation in Champaign, was organized in 1863. Their first small frame building was on the south side of Park street, just east of the present church. In 1877 the congregation bought the lot at the southeast corner of Park and Fourth and moved their building there. A larger brick church was built on that site in 1892 (pictured right, from Champaign County African American Heritage Trail marker on site).

Bethel served as a cultural center for the local African American community, establishing a library and supporting a church orchestra. The church served as a meeting place for Black students attending the University of Illinois, and it was the site where the local NAACP chapter was organized in 1915. The current church was built in 1959.

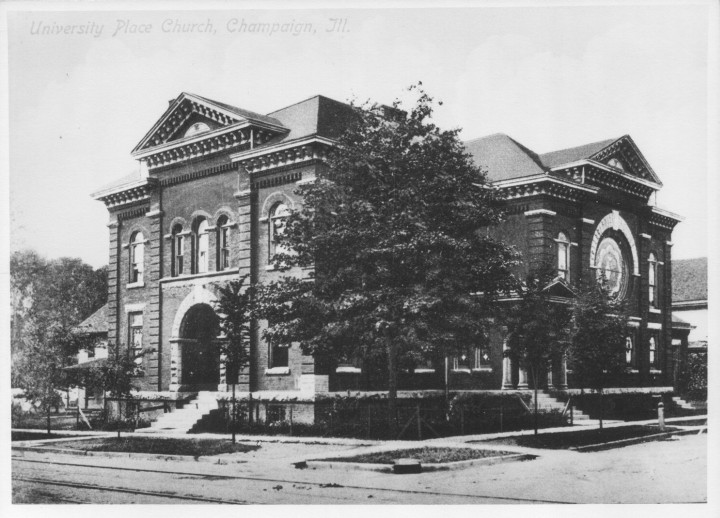

One additional “east side” church that shows up on early maps and city directories was a Christian Church congregation. It was organized in 1883 to serve both community and campus. Its first small frame building was on the north side of White between Sixth and Wright.

In 1902 the congregation moved two blocks south to a new brick building at the southwest corner of Wright and Springfield (below left), where it adopted the name University Place Christian Church. That building was lost in a 1914 fire. The present church (below right) at the southwest corner of Wright and Stoughton was dedicated in April 1936.

Changes that impacted Champaign’s Catholic community in 1912 bring us back to the west side of the Illinois Central tracks. St. John became the student chapel at the university. St. Mary continued to serve parishioners east of the tracks, and a new parish, Holy Cross, was created “to serve all Catholics west of the Illinois Central tracks.”

Soon after Holy Cross Parish was established, the block bounded by Clark, White, Elm, and Prairie streets was secured, and a building (pictured right) was erected in the northwest corner of the block. The Champaign Daily News (April 4, 1913) reported the structure was “built for the most practical use” with the church on the first floor and the second floor “equipped for a parochial school.” The first mass took place December 22, 1912. Dedication services were held April 9, 1913.

The original Holy Cross building continued to be part of the school complex until 1988. It was torn down to make way for parking space and a new parish hall.

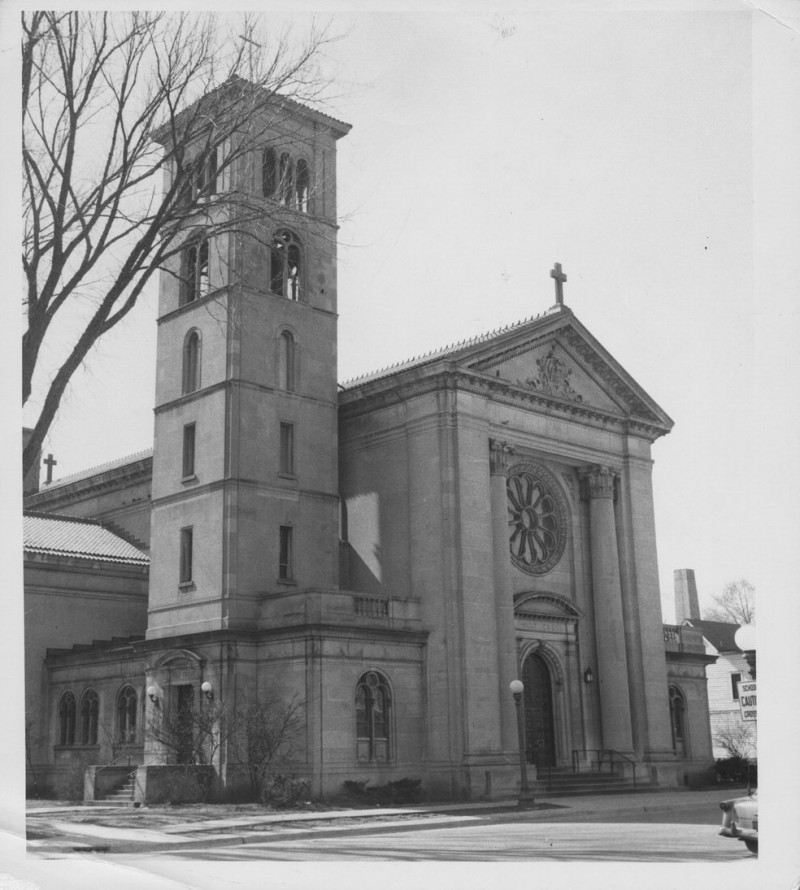

The current neo-classical building (pictured left), “The Church of the Exaltation of the Holy Cross,” was built between 1920 and 1924. Extensive interior renovations in 1983 overseen by celebrated local artist Harry Breen, a professor in the School of Art and Design at the University of Illinois.

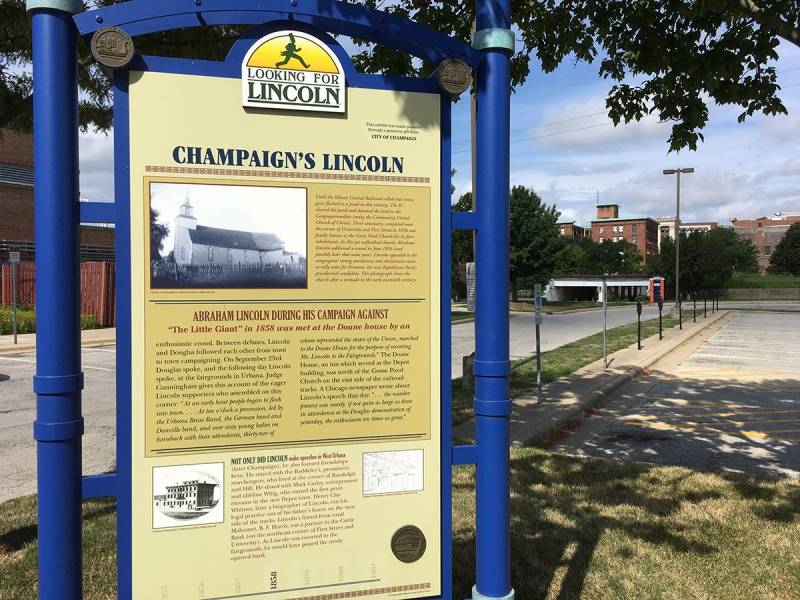

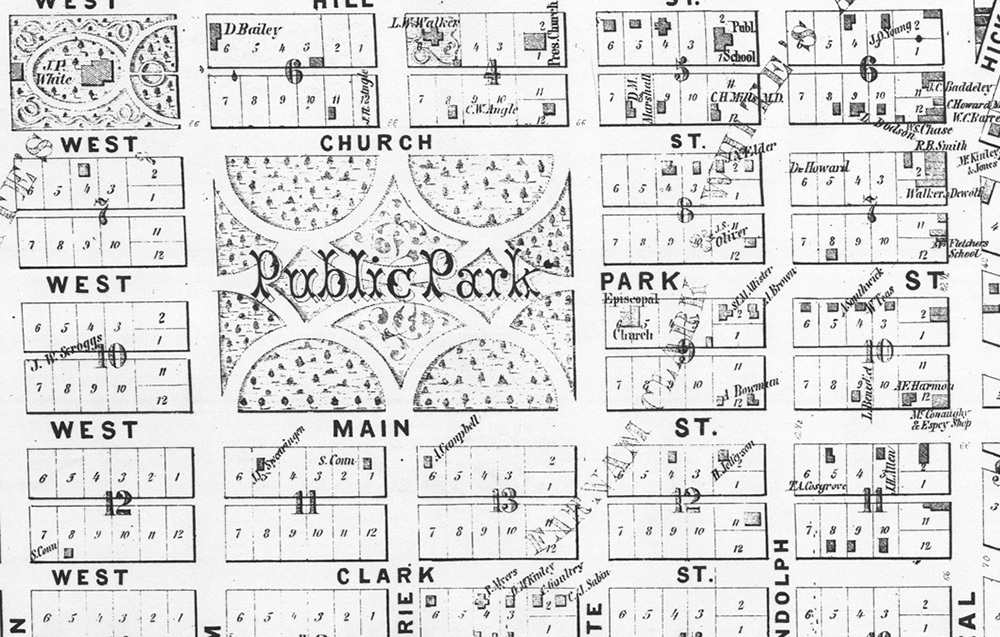

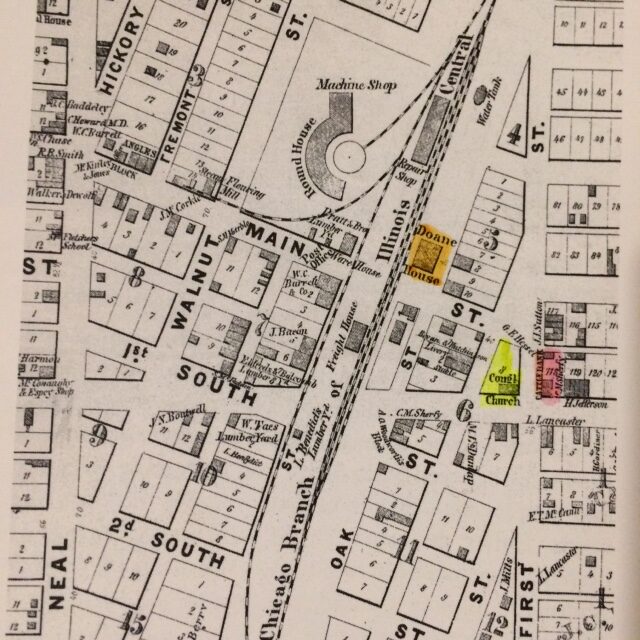

A section of the Birds Eye View of Champaign, 1884 (Illinois Library Digital Collections) below shows the locations of the “east side” churches in this article.

Sources consulted (in narrative order)

- “Historical Sketch,” in Community United Church of Christ Directory (1972)

- William C. Widenor and Dale Willard Robb, Heritage, Vision, and Mission: The First Presbyterian Church of Champaign, Illinois, 1850-2000 (2005)

- Natalia Belting, Beginnings: Champaign in the 1850s and 1860s (1960)

- A History of Saint John Lutheran Church: One Hundred and Fifty Years, 1955-2005 (2006)

- Olive Getchius & Wilson Zaring, Our Church: A History of First United Methodist Church (2007)

- First Baptist, Savoy website https://www.fbc-cs.org/im-new-3/history-of-fbc/

- Kathleen Wissmiller, A History of St. Mary Church (1974)

- In Grateful Remembrance, Celebrating 150 Years (St. Peter’s United Church of Christ, 2016)

- “History of Bethel A.M.E. Church,” typescript in Bethel A.M.E. vertical file

- A History of University Place Christian Church, 1883-1983 (1983)

- “Holy Cross Parish Seventieth Anniversary” (1982) and “Parish Scrapbooks” (1980s)