The Question of God, Part 5 (Freud Segment, “Human Mythology“; Lewis Segment, “From Spirits to God“; Panel Discussion, “Miracles“)

Freud was determined in his research and writing to demonstrate that religious sentiments could be traced to historical, cultural, and psychological influences that revealed themselves through the sacred stories of religious traditions. Rather than seeing truth in the midst of the story, he intended to reveal the mythical basis of all things sacred. The exclusive claims of Christianity, to Freud, derived from its imaginative connections with God’s promises to a Chosen People. The particular relationship these People enjoyed with God found its expression in the claims of a key historical figure, Moses. His influence, in turn, stemmed from a mythical tale connected to an archetypal son, the “declared favorite of a dreaded father.” To Freud, this primordial image of the favored son sacrificed by his brethren was the true basis of the Judeo-Christian worldview. It was a grand cultural deception which needed to be revealed and discarded.

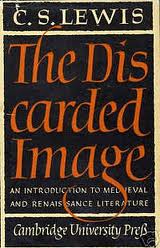

C.S. Lewis gave the title, The Discarded Image, to the last book he wrote. After a lifetime of teaching Medieval and Renaissance Literature, he gathered his lecture notes into a comprehensive thesis: while the “worldview” of this period may suffer from scientific and naturalistic “inaccuracies,” it represents a cohesive and imaginative picture of humanity that is more genuinely “true.” The Human “Image” that emerges from a pre-modern understanding of history, science, philosophy, and theology informed the most beautiful and influential literature in the Western world for its first two millennia. Writers of all genres during this period drew from a richer understanding of humanity to tell stories filled with imaginative and enchanted images that have been largely discarded by their modern counterparts. Most importantly, Ancient, Medieval, even Renaissance writers viewed the world itself and human experience as a cohesive, unified “whole” that found meaning outside of itself. Modernity has fragmented all things—including humanity—into segments of specialization subject to individual scrutiny and interpretation.

Freud’s effort to “mythologize” humanity’s religious impulse reflects the post-Enlightenment determination to explain and de-mystify every aspect of the human story. The result has been a world in which scientific analysis and empirical “accuracy” is the basis for truth and “fact.” One of his primary disciples, Carl Jung, pursued a different course, using psychoanalysis to explore a “collective consciousness” in humanity which mythical imagery reveals meaning. Jung’s famous “archetypes” provide the deep structure for human motivation and meaning. When we encounter them in art, literature, sacred texts, advertising—or in individuals or groups—they evoke deep feeling within us. These imprints, which are hardwired in our psyches, were projected outward by the ancients onto images of gods and goddesses. They continue to inform and motivate us in the present.

To Lewis and his fellow “Christian Humanists” (Chesterton, Tolkien, Dorothy Sayers, Evelyn Waugh, and others), modernity had gravely disenchanted the world and left us disconnected from important “essences” that define our true humanity. As Lewis finally accepts in this segment, Christianity is simply the “True Myth” from which all other stories draw their true meaning. “Here and here only in all time the myth must have become fact; the Word, flesh; God, Man. This is not ‘a religion,’ nor ‘a philosophy.’ It is the summing up and actuality of them all.”

Learn more about Humanism, Modernity, and the Human Story—

C. S. Lewis, The Discarded Image (originally published in 1964; Cambridge ed. 1995); Donald Williams, Mere Humanity: Chesterton, Lewis, Tolkien on the Human Condition (Broadman & Holman, 2008)