WARNING: Major spoilers from Captain America: Steve Rogers #1 to follow!!!

In honor of the 75th Anniversary of the publication of Captain America, Marvel Comics has chosen to dishonor their most iconic hero by turning him into a traitor.

Captain America: Steve Rogers #1, written by Nick Spencer, hit the stands this week with the jaw-dropping revelation that Steve Rogers, the original Super Soldier, is an operative of Hydra, the global terror organization rooted in the Axis powers of World War Two. As Captain America, Rogers has spent much of his heroic career—both in the comics, and now in the movies–fighting the very criminal cartel with which he’s now said to have a life-long connection.

(Marvel Comics, CA: Steve Rogers #1 by Jesus Saiz)

The idea is scandalous, outrageous, and nonsensical—and it will most likely sell a lot of comics as the story unfolds. But it also runs the risk of alienating many of Cap’s most devoted followers.

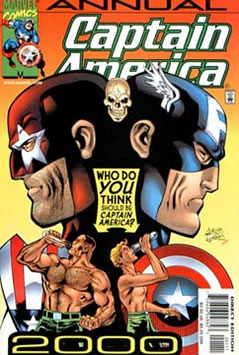

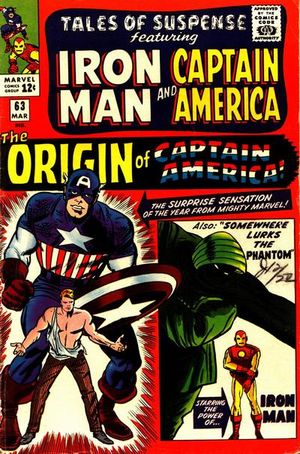

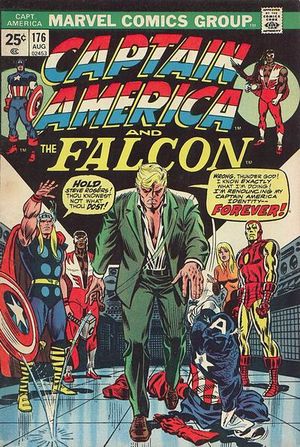

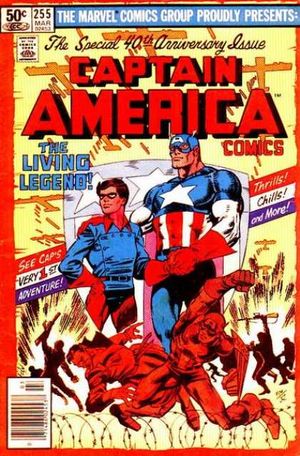

Marvel has meddled with the Good Captain many times over the decades: resurrecting him as a “man out of time” in the 1960s after he fell into comic-book obscurity after the war; having his arch-enemy, the Red Skull, inhabit a clone of his own body; killing him off (in the comics) after he opposed his own government in the original super-hero “Civil War”; resurrecting him again, only to have him revert to his natural age as an old man and pass the Captain America mantle on to someone else.

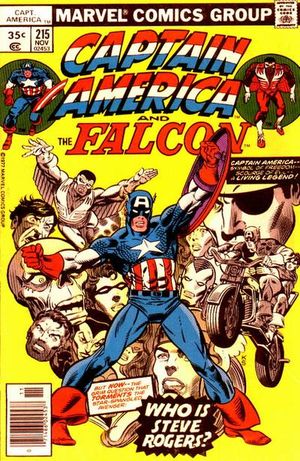

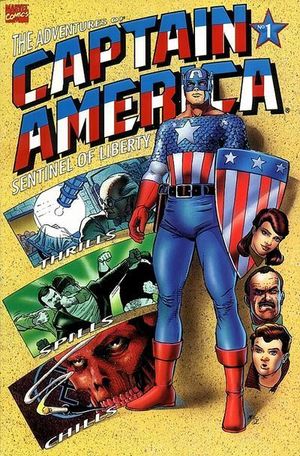

But in a recent Avengers story arc (again, in the comics), Rogers was restored once again to his prime. He’d just returned as a new iteration of the Living Legend–new uniform, new shield–and then made into a mockery everything that legend was built upon.

(Marvel Comics, cover for CA: Steve Rogers #1 by Jesus Saiz)

Of course, we’ve only so far seen the first issue of a story that “will go to some scary and shocking places if it hasn’t already,” Marvel Executive Editor Tom Brevoort told USA Today. What seems to be happening is genuine, Bevoort confirmed, promising in the same USA Today story that this is “really Steve Rogers and not some clone, shapeshifting Skrull, Life Model Decoy or a Cap from an alternate universe.”

If this does indeed prove true, the major hurdle Marvel, Bevoort, and writer Nick Spencer face is a seven-decade legacy of a heroic figure who’s every word and action over those years render the premise not only implausible, but absurd. Marvel has made great use over the years of the art of character “retconning,” a device used to make creative changes to past stories in order to “retroactively” bring them more clearly in line with current “continuity” developments. Captain America was, in fact, one of the first subjects of “retconning,” which was used to reconcile inconsistencies related to his return to the Marvel Universe in the 1960s.

(Marvel Comics, What If? #4, cover art by Gil Kane and Frank Giacola)

Marvel writer Ed Brubaker famously used the device not long ago to bring Cap’s long lost partner, Bucky Barnes, back to life, which crossed a continuity line long thought impenetrable. A complete reinterpretation of Marvel’s most iconic hero for the sake of sensation is much more than a clever retcon, however; it flies in the face of a long-standing commitment to coherent and cohesive continuity that has always been a hallmark of the famous “Marvel Universe.”

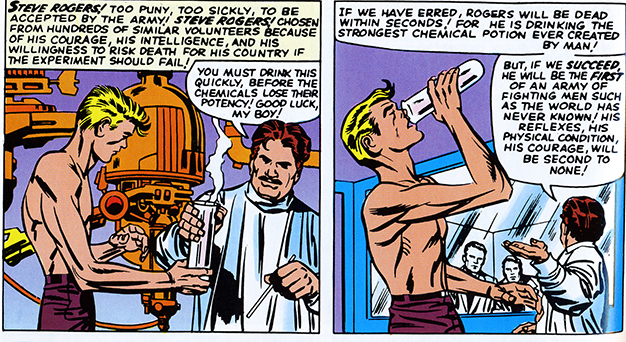

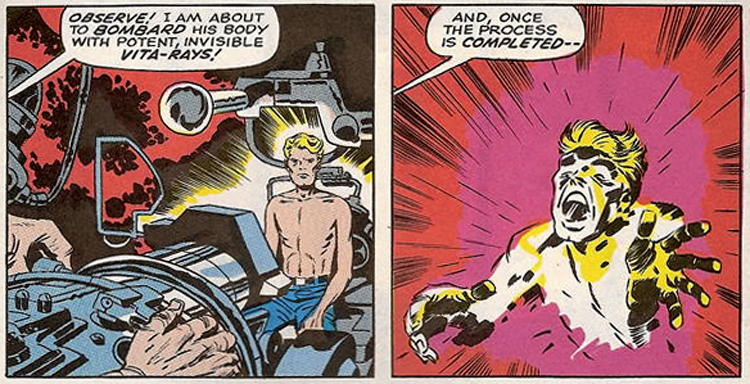

Captain America has undeniably changed with the times. Something that has remained steadfastly unchanged about him over the years, however, has been his unwavering sense of honor, devotion to duty, and strength of character. Much has been made in both comics and in the blockbuster Marvel movies that Steve Rogers is not simply the product of the procedure that made him a super soldier. Every effort to recreate the original process replicated its physical enhancements, but other subjects also developed mental and eventual physical dysfunctions, leading to erratic, unpredictable behavior.

What made Steve Rogers unique? The Captain America and Avengers films have particularly emphasized the importance of his moral sensibilities and strength of character. Dr. Erskine, the scientist who created the process, is certain that the super soldier serum, in some mysterious way, enhances not just a recipient’s physique, but also inherent aspects of personality and character. During his preparations, Erskine carefully examines Rogers’ motivations, probing more deeply into the nature of the man himself. When Steve asks before the procedure why he was chosen, Erskine responds, “Because the strong man who has known power all his life may lose respect for that power, but a weak man knows the value of strength and knows compassion. Whatever happens tomorrow you must promise me one thing: that you will stay who you are, not a perfect soldier, but a good man.”

(Paramount Pictures, Marvel Studios)

Writer Rick Remender explored the source of Rogers’ strength of character in a 2012 Captain America series. Young Steve’s father is revealed to be a broken, desperate man who brutalizes his wife and turns to drink in frustration. Sarah Rogers, by standing up to her husband and protecting her frail son, demonstrates many qualities that would one day define Captain America. On her deathbed, she tells her son, “Inside that small frame is a big, strong heart. A good man. A strong heart will take you further than any physical strength. A strong heart means you’ll never quit . . . you’ll always maintain the optimism of this great nation” (CA vol. 7 #11).

Nick Spencer has picked up this theme, but he’s given it a bizarre twist. One day a mysterious woman comes to Sarah Rogers’ rescue when she sees her being roughed up by her husband on the street. At a later meeting, the woman passes Sarah a pamphlet for the “New York Chapter of the Hydra Society” which extends an invitation for “all concerned citizens” to gather at a secret meeting. We are left to connect the dots between that invitation and Captain America’s fateful utterance, “Hail Hydra,” at the story’s end.

What is most unsettling about this proposition is the inference that somewhere behind the fascist origins and violent operations of a world terror organization is a kind-hearted, civic-minded social movement that feels the pain of “all concerned citizens.” History shows that more often, such groups gain strength first by telling citizens what (or who) the problem really is and then recruiting the convinced to be instruments of its destruction. It will take some clever and creative storytelling to convince most fans that there is some secret Hydra agenda that managed to turn America’s most patriotic symbol toward such despicable ends.

Perhaps the current sad state of American political culture warrants such a scandalous stab in the back. Certainly there is much to criticize about the excesses and injustices in modern American society as well as the bigotry and arrogance that pass themselves of as patriotism. No doubt these sentiments will be narrative elements of the story to come.

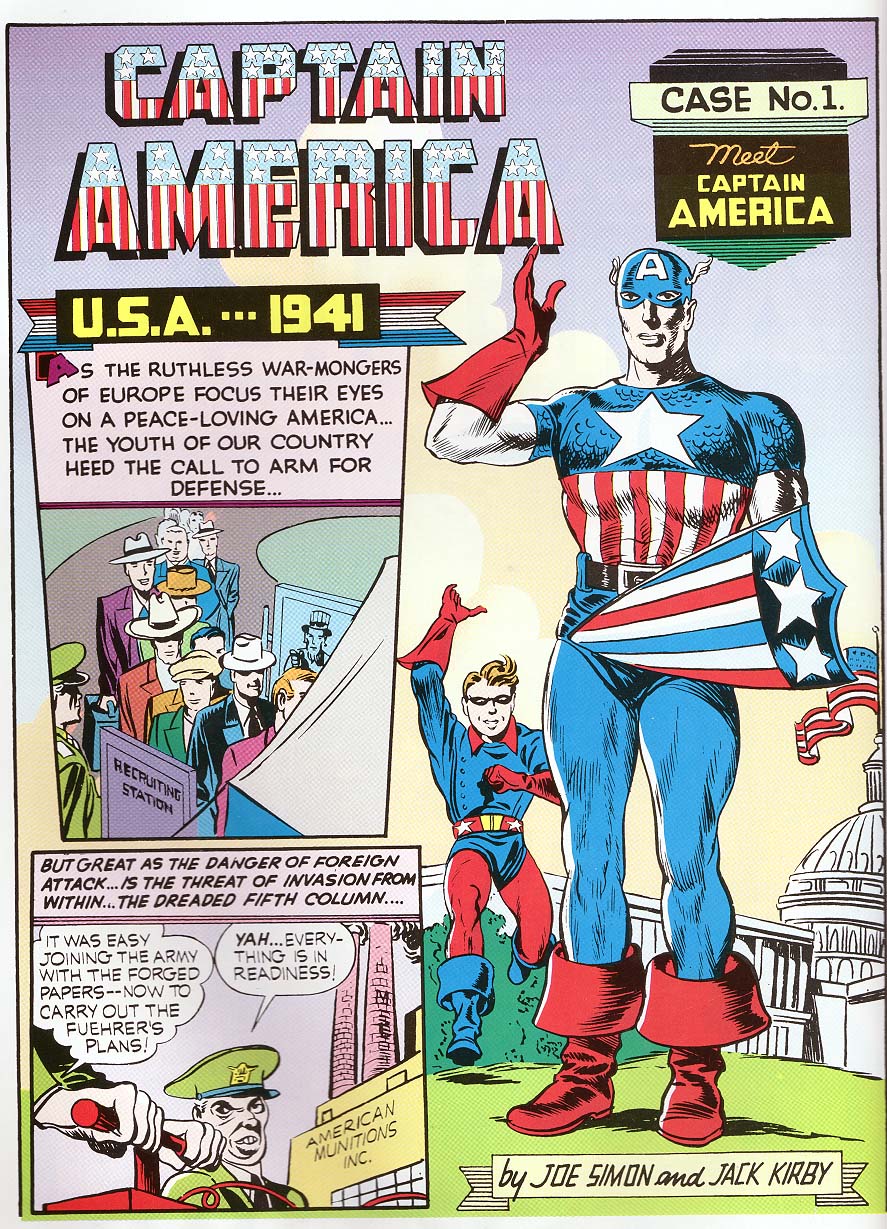

But Steve Rogers deserves better from Marvel than this manipulative mockery of his legacy, particularly during this anniversary year. Captain America is Marvel’s most iconic hero. Marvel’s first publication (then as Timely Comics) may have been called Marvel Comics, but Captain America was the first major Timely hero to be launched in his own (very successful) title. Even the Timely logo was fashioned after Cap’s original shield.

Hopefully the Good Captain will be given his proper due in the end. If not, his tarnished reputation will only add to the heap of harsh realities that motivated his demise. America still needs this “good man” with his “strong heart” to help her find her way.

Here are links to some of the major news articles related to this topic:

http://www.usatoday.com/story/life/2016/05/25/captain-america-comic-book-reveal/84896522/

http://time.com/4347224/captain-america-hydra-agent-marvel-tom-brevoort/