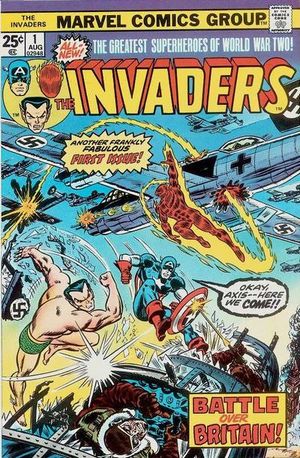

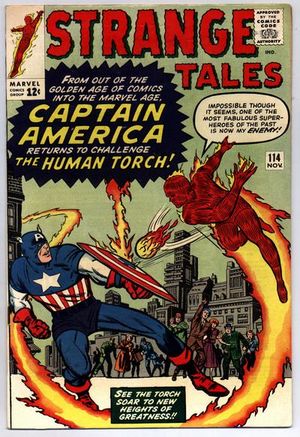

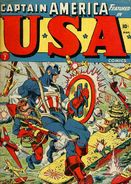

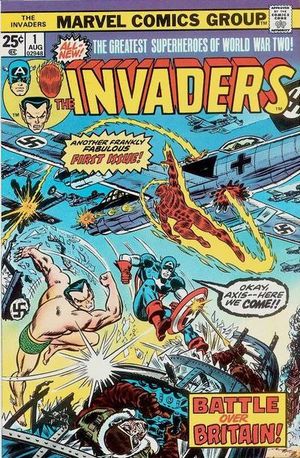

In 1975, Marvel Editor Roy Thomas took an ambitious step to more clearly connect and integrate Captain America’s “Golden Age” and “Marvel Age” storylines. “I’ve been waiting 30 years to do this one,” Thomas wrote in a commentary piece. “After all, hadn’t Captain America been created solely to protect our shores from the Nazis and the Japanese—to serve as a living symbol of the Land of the Free?”[1] Except for the first few issues, the action during the entire run of Invaders comics takes place during 1942. We’ll highlight all of their adventures together at once, then turn to other Invaders stories that take place later in the war.

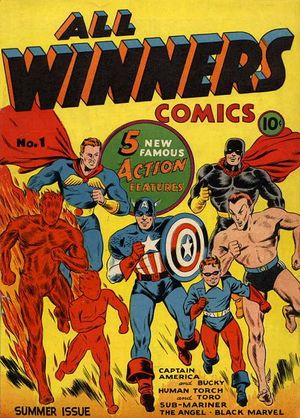

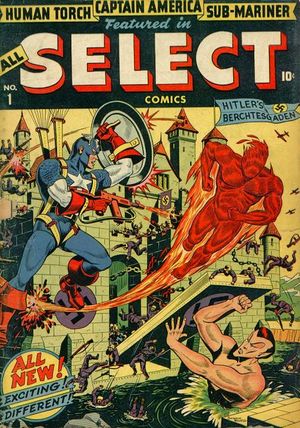

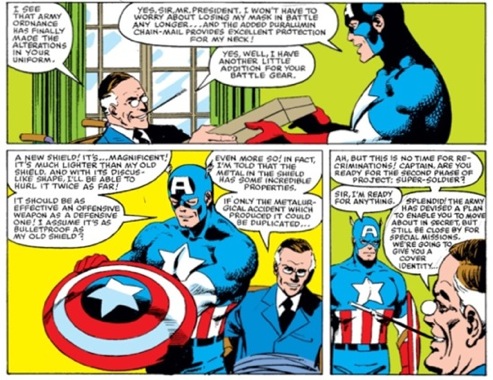

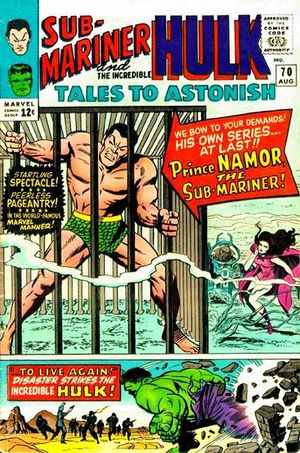

Giant-Size Invaders #1 opens “December 22, 1941” with Cap and Bucky fighting saboteurs on the docks near Washington, D.C. FBI agents inform Cap that “Dr. Anderson” (from the ToS #63 origin story) is dying and needs his help. Following this is a flashback of Cap’s origin story (drawn largely from ToS #63).[2] Cap and Bucky meet Anderson at Walter Reed hospital, where he relates the story of his discovery of a Nazi “super-soldier” program, which has produced a new threat: “Master Man.” Cap and Bucky are joined by the Human Torch, Toro, and Submariner to fight the menace; they save Winston Churchill, who dubs the team the “Invaders.”

G-S Invaders #1 (Frank Robbins, John Romita, G. Saladino; Invaders #1 (Romita & Saladino)

G-S Invaders #1 (Frank Robbins, John Romita, G. Saladino; Invaders #1 (Romita & Saladino)

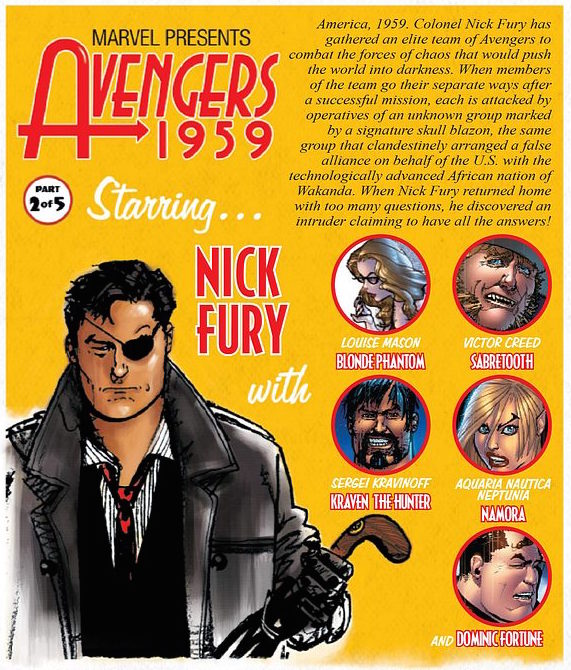

These proto-Avengers reassemble in late Dec. 1941 in response to seeming Teutonic versions of the Nordic Gods, who turn out to be aliens (#1-2)! In the early weeks of 1942 (#3-4) they save Churchill again, this time from a rogue Atlantean super-soldier dubbed U-Man. Churchill addressed a joint session of Congress Dec. 26, 1941 and traveled through the U. S. and Canada for four weeks; so this must be sometime before he returned to England. We also get a glimpse of Namor’s volatility here when he roughs up a U-boat captain to get information. As Cap stops him, Namor protests, “But – he’s a lousy Nazi!” The response is classic Cap:

And we’re no better if we start using their methods—beating up defenseless prisoners. We’re in the was, Namor, and we’re going to win it—but lets make sure we’re still the ‘good guys’ when we do! Or else—we don’t deserve to win.

Enraged, Namor goes after the renegade Atlantean himself, with a reluctant Bucky in tow.[3]

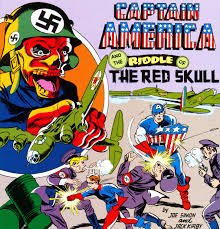

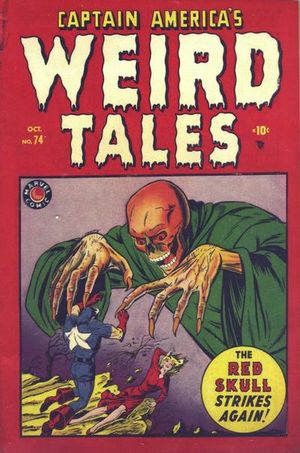

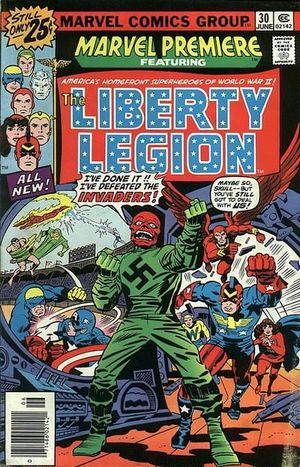

The Red Skull returns in issue #5. FDR remarks at a briefing, “he was presumed dead,” which connects nicely with the Skull’s last Golden Age appearance in CAC #7 (Oct. 1941). The Skull captures Cap, Torch, Toro, and Namor, leaving Bucky behind as “of little use.” In a story that weaves through Marvel Premier #29-30 and Invaders #6, Thomas reintegrates several Golden Age heroes into the “modern” Marvel Universe as members of the home-front “Liberty Legion.”[4] MP #30 introduces NY Yankees batboy Fred Davis, who plays “Bucky” in a ruse to lure the Red Skull to his defeat (and will later figure prominently in Thomas’s reworking of Cap & Bucky’s end-of-the-war “demise”).[5]

Invaders #6 (Jack Kirby, Joe Sinnott, Saladino); Marvel Premier #30 (Kirby, Frank Giacoia)

Invaders #6 (Jack Kirby, Joe Sinnott, Saladino); Marvel Premier #30 (Kirby, Frank Giacoia)

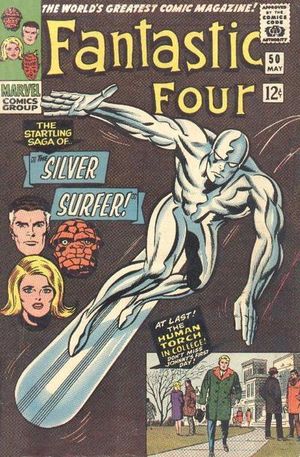

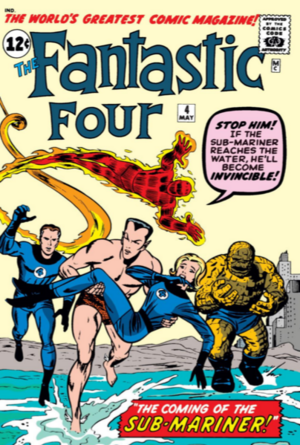

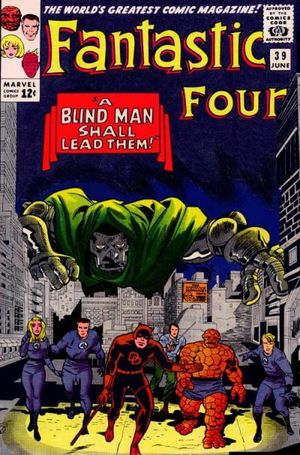

In Fantastic Four Annual #11 (1976), the FF travel back in time to “Early 1942,” arriving in the middle of a meeting in London in which the Invaders are being briefed about the “Nazis planning something big” in occupied France. A container of Vibranium, sent to the past by Doom’s time machine, has given Germany a technology advantage which they will use to win the war (alternate future/time paradox and all that!). The Invaders team up with the FF, traveling to France and encountering Baron Zemo. This story depicts Cap’s first battle with Baron Zemo, resulting in the “Adhesive X” incident that permanently fixed Zemo’s hood to his face. The FF return to the present having retrieved only half of the missing Vibranium. It’s up to Ben Grimm, the Ever-Lovin’ Thing, to return to 1942 himself to finish the job (Marvel Two-In-One Annual #1 and MTIO #20 (both 1976). This time Grimm teams up with the Liberty Legion to battle Master Man, Warrior Woman, U-Man, and SkyShark, stopping the Nazis from developing a prototype “Flying Swastika” sky fortress.

The Invaders saga moves to England in mid 1942 (#7-11), introducing the original Union Jack (Lord Montomery Falsworth, a member of a WWI team called “Freedom’s Five) and his daughter Jacqueline. Falsworth’s brother Jonathan turns out to be the Nazi super-vampire Baron Blood. When Jacqueline is bitten by the vampire, a blood transfusion from the Human Torch interacts with the vampire venom in her bloodstream, giving her super-speed. She takes the costumed identity “Spitfire” and eventually joins the Invaders. Baron Blood is impaled, but Lord Falsworth’s legs are crushed, ending his brief career as the first Union Jack in the Invaders.[6]

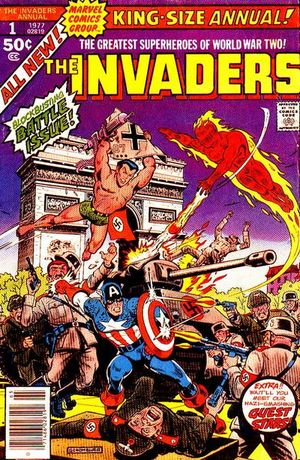

Fantastic Four Annual #11 (Kirby, Sinnott); Invaders Annual #1 (Alex Shomburg)

Fantastic Four Annual #11 (Kirby, Sinnott); Invaders Annual #1 (Alex Shomburg)

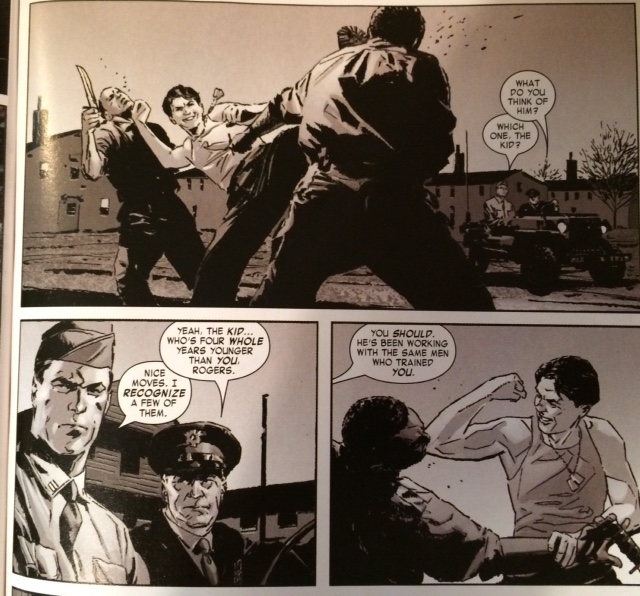

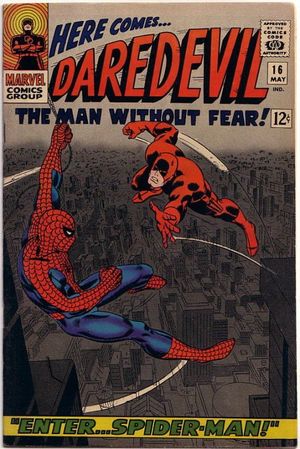

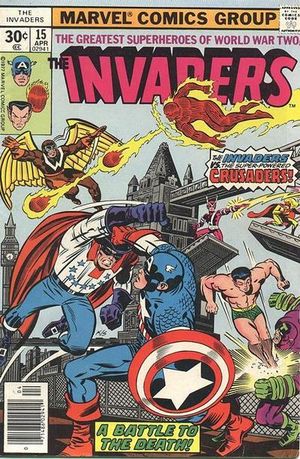

After travelling to the Warsaw Ghetto in Poland to rescue a Jewish boy who has the ability to turn into the super-human Golem of Hebrew myth (#12-13), the team returns to London and encounter a group of British superheroes called the Crusaders. The team includes one Yank–The Spirit of ’76–and the diminutive Dyno-mite, later revealed to be Roger Aubrey, a close friend of the missing Falsworth heir, Brian (#14-15).[7] The team’s next adventure (#16-21) takes them to Germany, where they face Master Man, his new “mate,” Warrior Woman, and Hitler himself! This storyline is precipitated when Nazis kidnap G.I. Biljo White, who turns out to be the creator of a popular Cap knock-off comic, Major Victory. Since that hero’s origin story was a thinly-veiled imitation of Cap’s own, seems “the Nazis may suspect that a comic book artist . . . knows something about the carefully-guarded Super-Soldier Formula!”[8]

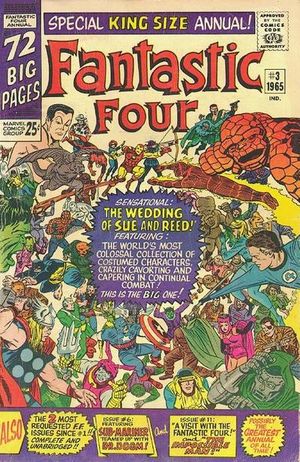

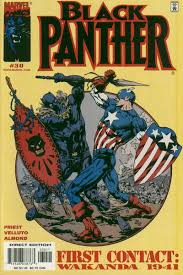

Thomas took advantage of a summer Annual to return to events first depicted in a “pre-Invaders” time travel story he’d written in Avengers #71 (Dec. 1969). both stories repr. in GS Avengers/Invaders #1, 2008). In the original Avengers story, Cap, Black Panther, and Yellow Jacket travel back in time to Paris in the summer of 1942 (“1941” in the Avengers story), where they battle Namor, the Human Torch, and—Captain America! This time the story is told from the Invaders’ point of view, reconciling, as much as possible, every little detail which had not been considered in 1969 (including the mistaken dating)![9]

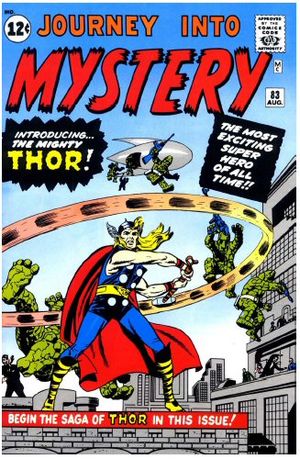

The subject of Japanese-American internment during the war is tackled when the team travels to California to seek medical treatment for the wounded Toro (#25-26). When they find most qualified surgeon for the task (a Japanese-American) and his family have been sent to the camps, Cap rips into the openly racist camp C.O.: “These people–herded here like so many animals! While we’ve been off fighting the Fascists, has our own country taken a page from our enemies?” With Bucky and Toro remaining state-side, Cap, Torch, and Namor return to Europe, reconnecting with Spitfire and Union Jack to confront a new menace: Komtur, the Teutonic Knight. Meanwhile, Bucky and Toro form a new team of youngsters called “Kid Commandos” and Hitler finds a way to summon Thor (yes, the actual MU God of Thunder) to aid the Nazi cause! (#28-34).[10]

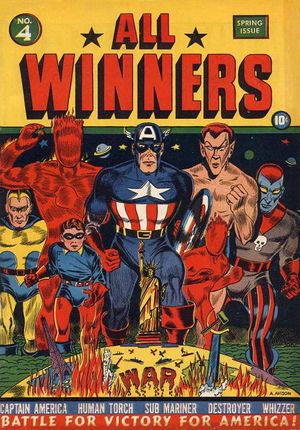

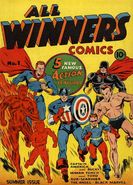

The Liberty Legion returns for a run (#35-37) in which Golden Age heroes the Whizzer and Miss America replace Union Jack and Spitfire on the team. A new Nazi menace, the Iron Cross, also makes his first appearance. The first Invaders series winds up (#38-41) in something of a mega “All Star” bout featuring the now “All-Winners Squad”-styled team of Americans against Baron Blood, Master Man, Warrior Woman, Merrano, and a new Asian villainess called Lady Lotus. Nothing like going out swinging!

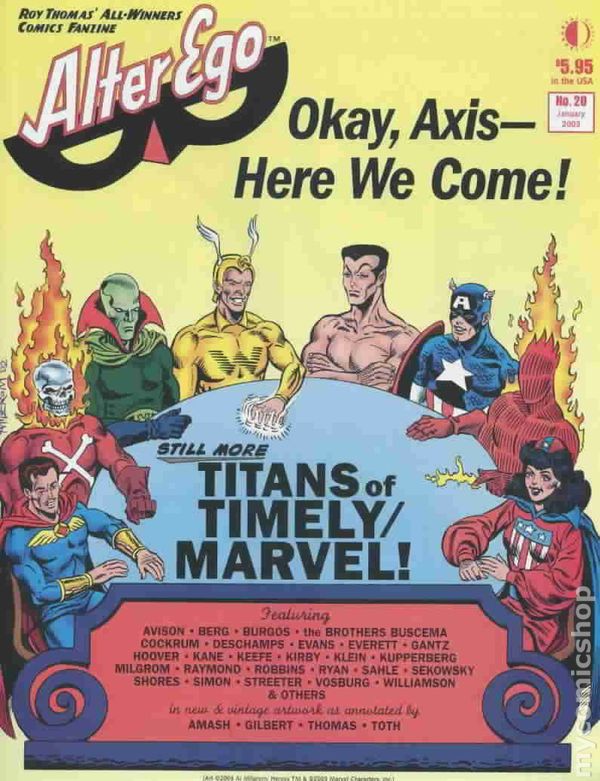

Invaders #15 (Kirby, Sinnott) Alter Ego #20 (Al Milgrom)

Invaders #15 (Kirby, Sinnott) Alter Ego #20 (Al Milgrom)

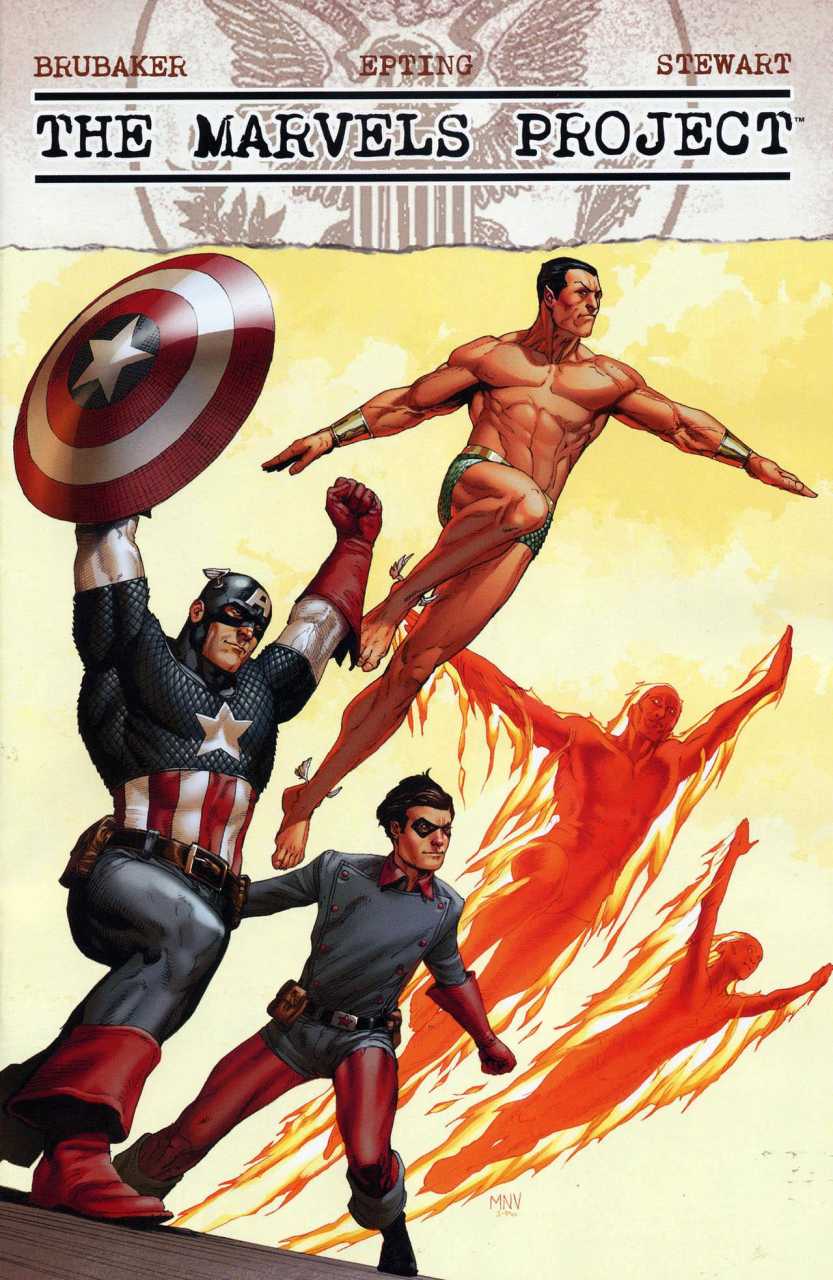

“For yours truly,” Thomas later reflected, “The Invaders was always, despite its World War II setting, a giant stage on which almost any drama could be played—or any type of homage be paid to heroes and/or villains of yesteryear . . . .”[11] For Captain America, it foreshadowed his later role as “The First Avenger,” placing him in a team context for the first time (chronologically, at least).

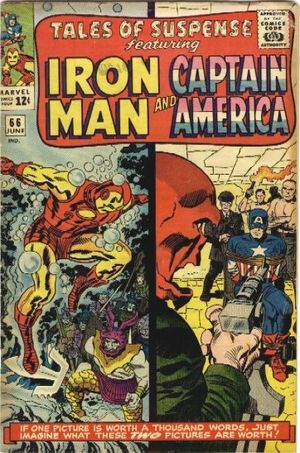

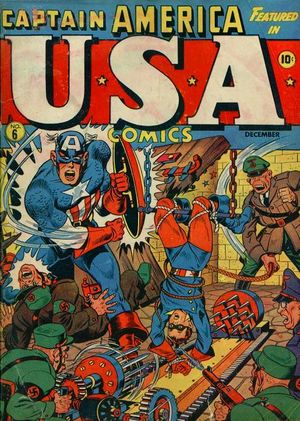

[1] Giant-Size Invaders #1 (June 1975). The Invaders series was more than just an imaginative presentation of war-time action. Thomas determined to bring together the “old-style long-on-action-short-on-sense” style of stories of the Golden Age with the “sensational super-villains which are such an integral part of today’s comics scene.” Yet he was also very specific about maintaining flexibility in the connections between past and present. Events in Golden Age stories may have “actually happened, more or less, [but] we’re ordinarily not going to consider ourselves bound by anything which occurred in the old Timely mags unless we also verify it in the ‘Invaders’ tales themselves” (he even specifically mentions a story in CAC #9 (Dec. 1941; though he writes #7) to head off objections to his dating the first Invaders story on December 22, 1941). Still, few people (except, perhaps, Ed Brubaker) have done more give Golden Age characters contemporary relevance. Early issues of Invaders are peppered with Thomas’s wonderful “Nostalgic Notes on the Golden Age of Comics.”

[2] Thomas also “reconciled the ‘Dr. Reinstein’ of CAC #1 and the ‘Dr. Erskine’ . . . of ToS #63” in this Invaders story (“World War II Forever (But Only In Comic Books!), Alter Ego #20 (Jan. 2003), p. 6. In this article, Thomas provides many insights into the creative process behind the Invaders, his various reinterpretations of Golden Age heroes, as well as a general synopsis of each story in the title’s 41-issue run.

[3]Invaders #3 (Jan. 1976), Thomas. The opening scene of issue #4, with Cap, Torch and Toro in “hot” pursuit across a D.C. Army Air Corps base, is later recalled by journalist Ben Urich in Conspiracy #1 (Feb. 1998).

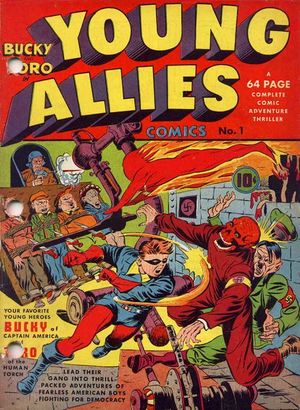

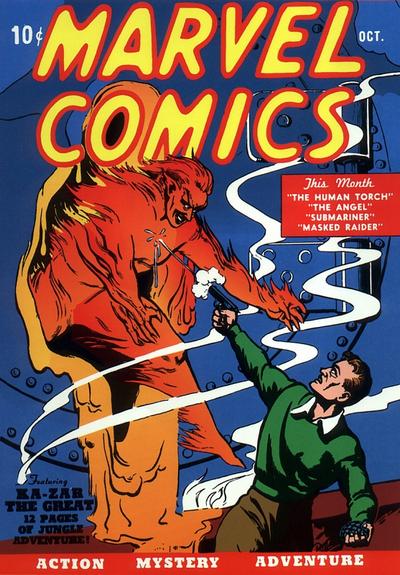

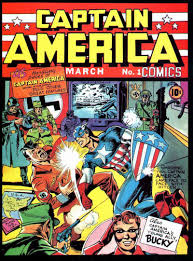

[4] The Liberty Legion was formed in June 1942, according to CA:Patriot #1 (2010). When Cap makes specific reference to the Patriot in Invaders #5, Bucky protests: “Aw, get serious, Cap! He may wear your colors, but he’s not in your league!” Cap chastises him: “They’re not ‘my colors’, lad. They belong to 134,000,000 Americans.” This issue also shows Bucky and Toro reading early issues of Captain America Comics and Marvel Mystery Comics. Bucky points to two defects in the stories: “they’ve got a lot of details all wrong” and “they have us fighting most of our battles here in the states.”

[5] After Cap and Bucky’s “death’” near the war’s end, Davis will ultimately become the new Bucky for real along side William Naslund and Jeff Mace in the late 1940s (see “Post-War Caps” below). Davis also will later join the V-Batallion and become a member of the revived Penance Council in 1951. For more on the reintegration of Golden Age Heroes in the “modern” MU, see Appendix 1.

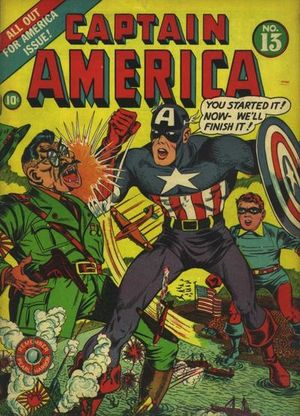

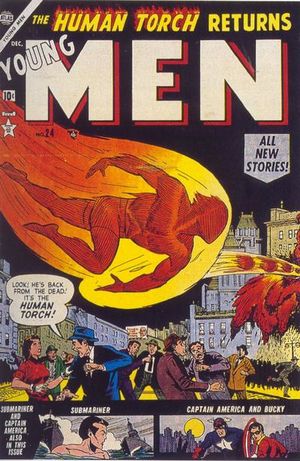

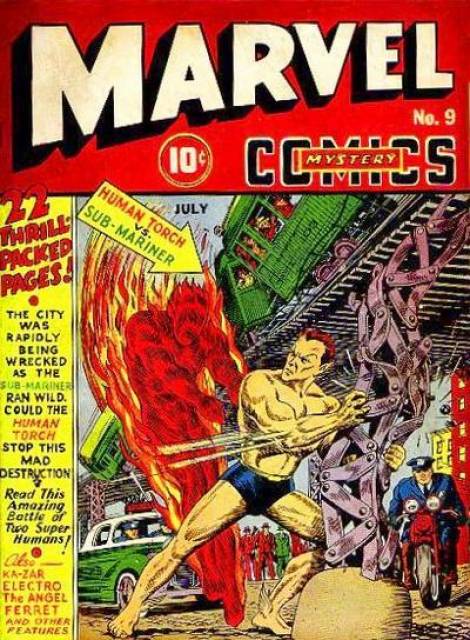

[6] In the midst of this arc (issue #10), Thomas makes a direct connection between Cap’s Invaders activity and an actual Golden Age story. Reflecting on Lord Falsworth’s recent brush with death, Cap recalls “The Reaper . . . the Nazi foe [Bucky] and I fought months ago back in the states.” Noting that while the “hard facts” of the encounter remained classified, “A basically accurate account of it is going to be published state-side, any day now. The comic book version’ll be called – “Captain America Battles the Reaper!” The remainder of the story reprints the original tale from CAC #22 (Jan. 1943). Thomas will also use the Invaders platform to reinterpret Toro’s origin (#22) and reprint (in #24) an early team-up between Torch and Namor from MMC #17 (March 1941).

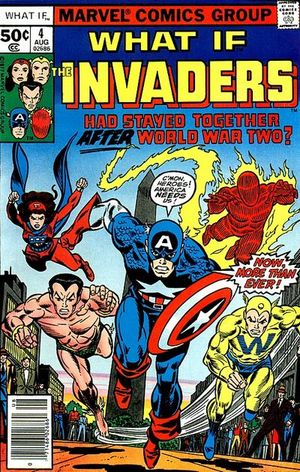

[7] In his previously mentioned Alter Ego article, Thomas the Crusaders were designed with specific “Golden Age lineages” in mind. The Spirit of ’76, “clearly based on Nedor’s Fighting Yank,” will be used again by Thomas just a few months later in his classic What If? #4 reinterpretation of Cap’s 1945 “demise” (Aug. 1977; see more in “Post War Caps” below). Brian Falsworth is revealed to be Golden Age hero the Destroyer in Invaders #18 (he then becomes second Union Jack in #21, and Aubrey takes up the role of the Destroyer). See more details on Thomas’s reinterpretation of these characters in Appendix 1.

[8] Biljo White, an actual artist and friend of Thomas’s, was not only featured in the story as a fictional version of himself, he even drew the artwork of Major Victory’s origin story in a full-age “comic within a comic” (#16). Major Victory was an actual Golden Age hero who appeared in 1941-42 issues of Chesler’s Dynamic Comics and Yankee Comics (as related in Thomas’s Alter Ego article).

[9] Invaders Annual #1 (1977). This tale fits between events in Invaders #15 & #16 and includes a nice editorial from Thomas carefully explaining the connections with the original Avengers story.

[10] Issue #29 includes a flashback to Cap & Bucky’s first encounter with Komtur in late 1941, “some weeks before there was a team called the Invaders.” The Kid Commandos include a Japanese-American girl (“Golden Girl”) and an African-American boy (“Human Top”). The Thor encounter ends with the Thunder God coming to his senses, but wiping the memory of his appearance from everyone (albeit with a nod to Avengers future): “’Twas not meant that Thor should walk amongst mortals at this time. Mayhap one day, ere long, as ‘twas prophesied . . . .” The story also features a cryptic appearance by time travelling Victor von Doom, his face wrapped in bandages.

[11] “World War II Forever . . .” Alter Ego (Jan. 2003).